Parallel Solutions in C#

Introduction

The age of parallel computing has arrived, and now, even us programmers have the burdensome task of taking what was once simple sequential code and making it run on parallel processors. There are so many painstaking details to keep track of - iterators, load balancing, starvation, data sharing, synchronization, … Yeah, I think you get the point. It’s enough to drive one mad. So, if this the way of the future, how does one keep from losing their mind amidst the chaos?

The Way Forward

No, fear not my programming denizens, we have an answer that comes in the form of the .NET (Task Parallel Library (TPL))[1]. If you’re not familiar, don’t worry, we will walk through a few examples of transforming sequential code into parallel, and hopefully by the end, the angst of parallel programming will be a thing of the past.

The Task Parallel Library works very similar to many of the parallel frameworks used in C++ (OpenMP, Intel Thread Building Blocks, and Micorosft Parallel Patterns Library), in that we are given parallel structures that are very similar to the sequential iteration syntax we are already familiar with. For example, the for and foreach have the equivalents Parallel.For and Parallel.Foreach that work very simliar to their sequential counterparts. Next, we’ll talk about these tools and how they can be used to simplify your code. And lastly, we’ll cap it all off with an example of converting sequential code into parallel code by creating a fractal image using the Mandelbrot set.

Source: Compiled in VS2013, .Net 4

The Mechanics

So, let’s do something basic. We’ll show a few variations of the transformation of an index-based sequential loop into a parallel one.

Let’s say we want to multiply some huge set (like 1 million plus elements) by a scaling factor, and we want to utilize the power of multiple cores to do it. Well, we can begin by writing the code sequentially.

double scale_factor = 3.5;

for (int index = 0; index < elements.Length; index++)

{

elements[idx] = elements[idx] * scale_factor;

}

This can then be converted into the following equivalent parallel code.

double scale_factor = 3.5;

Parallel.For(0, elements.Length-1, // range is inclusive

(index) =>

{

elements[index] = elements[index] * scale_factor;

}

);

Simple, eh? Yes, it’s really that easy. Just make sure you include the System.Threading.Tasks.Parallel assembly and you’re ready to begin harnessing the power of multiple cores.

Under the Hood

Now, let’s talk about what’s going on under the hood. The TPL takes your loop and creates a thread for each core of the computer. It then partitions the loop among the number of threads. In the past, this was all done manually by you, the programmer, and although it sounds simple, even this most basic example can easily suffer from thread starvation or improper indexing, which may even miss some elements entirely (it’s surprisingly difficult to implement proper indexing for threads). This is why we can release this burden from our minds, and let the powerful TPL handle the mundance mechanics of thread synchronization. However, although our speedup will be quite noticable, especially for large sets; it is important to remember that the speedup from multiple cores is NOT linear. You’re speedup will only be as great as you’re slowest thread. And even though the .NET framework tries to do a good job at partitioning the set to balance the work load, it is highly unlikely that each thread will do the same amount of work. If you’re curious about why this is, take a look at what Gene Amdahl says about it. [2]

Here’s another, slightly more complex example. This time we will aggregate the elements using a sum. This requires us to use a mutex to lock our shared data (the sum).

double sum = 0.0;

double scale_factor = 3.5;

for (int index = 0; index < elements.Length; index++)

{

for (int innerIndex = 0; innerIndex < index; innerIndex++)

sum = sum + element[innerIndex] * scale_factor;

}

And the corresponding parallel code:

double sum = 0.0;

double scale_factor = 3.5;

object mutex = new object();

Parallel.For(0, elements.Length - 1, // range is inclusive

(index) =>

{

double local_sum = 0.0;

for (int innerIndex = index; innerIndex < index; innerIndex++)

local_sum = local_sum + elements[innerIndex] * scale_factor;

lock (mutex)

{

sum += local_sum;

}

}

);

This parallel transformation is slightly more complex since we now have to ensure that the threads don’t all access the shared data at once. This is what’s known as a race condition, and is another one of the difficulties of writing threaded code. I won’t go into detail about the different hazards involved in writing threaded code, but a race condition basically occurs when the output depends on a sequence of inputs. In our example, it is possible that the sum can be overwritten using an older version of itself. If it sounds weird, it is, but it happends, and is a source of major frustration for large-scale multithreaded applications.

The Fun Stuff

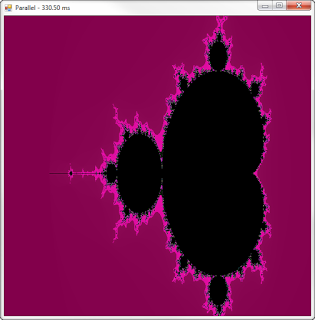

Okay, now that we’ve gotten a bit of the techno babble out of the way, let’s make something cool. I’ve always been fascinated with fractals, as they seem like such elegant structures, and the fact that they are natural phenomenon occurring throughout nature, gives them a sort of mysterious intrigue.[3] The Mandelbrot Set is one such fractal. It is essentially calculated by feeding a point, c, into the complex function, \(f(z) = z^2 + c\) , and iterating upon previous values of \(f(z)\) , and if the function tends to infinity it is not in the Mandelbrot Set, and we generally denote this by coloring the point. I won’t go into too much detail about this, as internet resources[4] can give a much better explanation than I can, but I do want to draw attention to just how easy it is to translate the algorithm from sequential to parallel, and just how much of a performance boost is possible with parallel code. Don’t worry, although I don’t explain the algorithm, this code, and the source example have been liberally commented.

private Pixel[,] GenerateMandelbrot(int width, int height, double realMin, double realMax, double imagMin,

double imagMax, int iterations, List<Color> colorSet, bool runParallel = false)

{

// info on mandelbrot and fractals

// https://classes.yale.edu/fractals/MandelSet/welcome.html

Pixel[,] image = new Pixel[width, height];

// scale for cartesian -> complex translation

double realScale = (realMax - realMin) / width;

double imagScale = (imagMax - imagMin) / height;

if (runParallel)

{

// Parallel Version

Parallel.For(0, width,

(xPixel) =>

{

for (int yPixel = 0; yPixel < height; yPixel++)

{

// complex plane is similar to cartesian,

// so translation just requires scaling and an offset

// (x, y) => (real, imag) = (realScale * x + realMin, imagScale * y + imagMin)

Complex c = new Complex(realScale * xPixel + realMin, imagScale * yPixel + imagMin);

Complex z = new Complex(0, 0);

// black is the default

// assumes point will be in the mandelbrot set

// iterations will determine if it is not

image[xPixel, yPixel] = new Pixel(0, 0, 0);

for (int iterIdx = 0; iterIdx < iterations; iterIdx++)

{

// the basic iteration rule

z = z * z + c;

// does it tend to infinity?

// yes, it seems strange, but there is a proof

// for this (https://classes.yale.edu/fractals/MandelSet/JuliaSets/InfinityProof.html)

// Essentially, if the distance of z from the origin (magnitude), is greater than 2

// then the iteration will go to infinity, which means it is NOT in the mandelbrot

// set

if (z.Magnitude > 2.0)

{

double percentage = (double)iterIdx / (double)iterations;

Color chosen = colorSet[(int)(percentage * colorSet.Count)];

image[xPixel, yPixel].FromColor(chosen);

break;

}

}

}

});

} else

{

// Sequential Version

for (int xPixel = 0; xPixel < width; xPixel++)

{

for (int yPixel = 0; yPixel < height; yPixel++)

{

Complex c = new Complex(realScale * xPixel + realMin, imagScale * yPixel + imagMin);

Complex z = new Complex(0, 0);

image[xPixel, yPixel] = new Pixel(0, 0, 0);

for (int iterIdx = 0; iterIdx < iterations; iterIdx++)

{

z = z * z + c;

if (z.Magnitude > 2.0)

{

double percentage = (double)iterIdx / (double)iterations;

Color chosen = colorSet[(int)(percentage * colorSet.Count)];

image[xPixel, yPixel].FromColor(chosen);

break;

}

}

}

}

}

return image;

}

Yes, literally changing the for to Parallel.For is the only difference between the sequential and parallel versions of the code. Now, checkout the difference in runtimes.

The parallel version is almost twice as fast running on my 2 cores. Now imagine if you had 4, 8, or even 16 cores running, and you can begin to envision just how critical parallel execution can be for improving the performance of your programs. If you haven’t yet, I urge you to also try compiling and running the source code. It was compiled with Visual Studio 2013, but if you aren’t able to open the solution, the source code should compile and execute in any .NET 4+ environment. And, even if you just want to play around creating fractals, this code generates Mandelbrot fractals from a random color palette with the ability to zoom so you can play around with the settings and generate some really mindbending fractal patterns. Have fun!

Wrap-Up

Hopefully, this has helped dissolve some of the apprehension felt when faced with creating parallel code. Using C# and the TPL we were able to simplify the creation of parallel algorithms using control structures that we’re already familiar with. I should also mention that there is a way of using the TPL with Linq, and examples of this, and more complex uses of the TPL are available on MSDN[1]. I’ve left a link below if you’re curious. The hertz rush is gone, and now we must be a bit more savvy when mining for peformance by parallelizing our code to harvest the potential of multiple cores.

You made this very easy to grasp, excellent post.

ReplyDelete